Jan 26, 2026

The architecture of data storage has evolved rapidly from traditional Data Warehouses to Data Lakes, and now, to the Lakehouse. While formats like Apache Iceberg and Delta Lake have standardized the “Table Format” layer by bringing ACID transactions to file-based storage, they often introduce significant complexity in metadata management.

In this post, we explore DuckLake, a format that reimagines the Lakehouse by managing metadata in a standard SQL database rather than thousands of meta files. We will compare it to existing architectures, deep dive into its internal mechanics (concurrency, compaction, inlining), and discuss the future of integrating this engine with PostgreSQL and DuckDB.

The Lakehouse Architecture

Before diving into DuckLake, let’s first look at the evolution of modern data architecture.

Data Warehouse

The Data Warehouse is designed for high-performance analytics or OLAP workloads. It follows a strict Schema-on-Write philosophy: data must be cleaned, structured, and defined before it can even enter the system.

Pros: Extremely fast query speeds, strict ACID transaction support, and high data quality.

Cons: High storage/compute costs, rigid scalability, and an inability to handle unstructured data (like images, video, or raw logs). It is often a closed architecture.

Data Lake

The Data Lake emerged as a response to the volume and variety of Big Data. It acts as a central repository (typically built on AWS S3 or HDFS) that stores everything in its raw format. It follows a Schema-on-Read philosophy: store now, define structure later.

Pros: Extremely low storage costs, pay-as-you-go compute costs, and supports all data types (structured, semi-structured, unstructured), and offers near-infinite capacity.

Cons: Without strict governance, it easily becomes a “Data Swamp.” Crucially, Data Lakes natively lack support for transactions; concurrent reads and writes can easily lead to errors or data corruption, and query performance generally lags behind warehouse.

Lakehouse

The Lakehouse is the convergence of these two paradigms. It builds upon the cheap, flexible storage of a Data Lake but introduces a sophisticated “Metadata Layer” (such as Apache Iceberg, Delta Lake, or our own DuckLake) to enforce management capabilities previously only found in Warehouses.

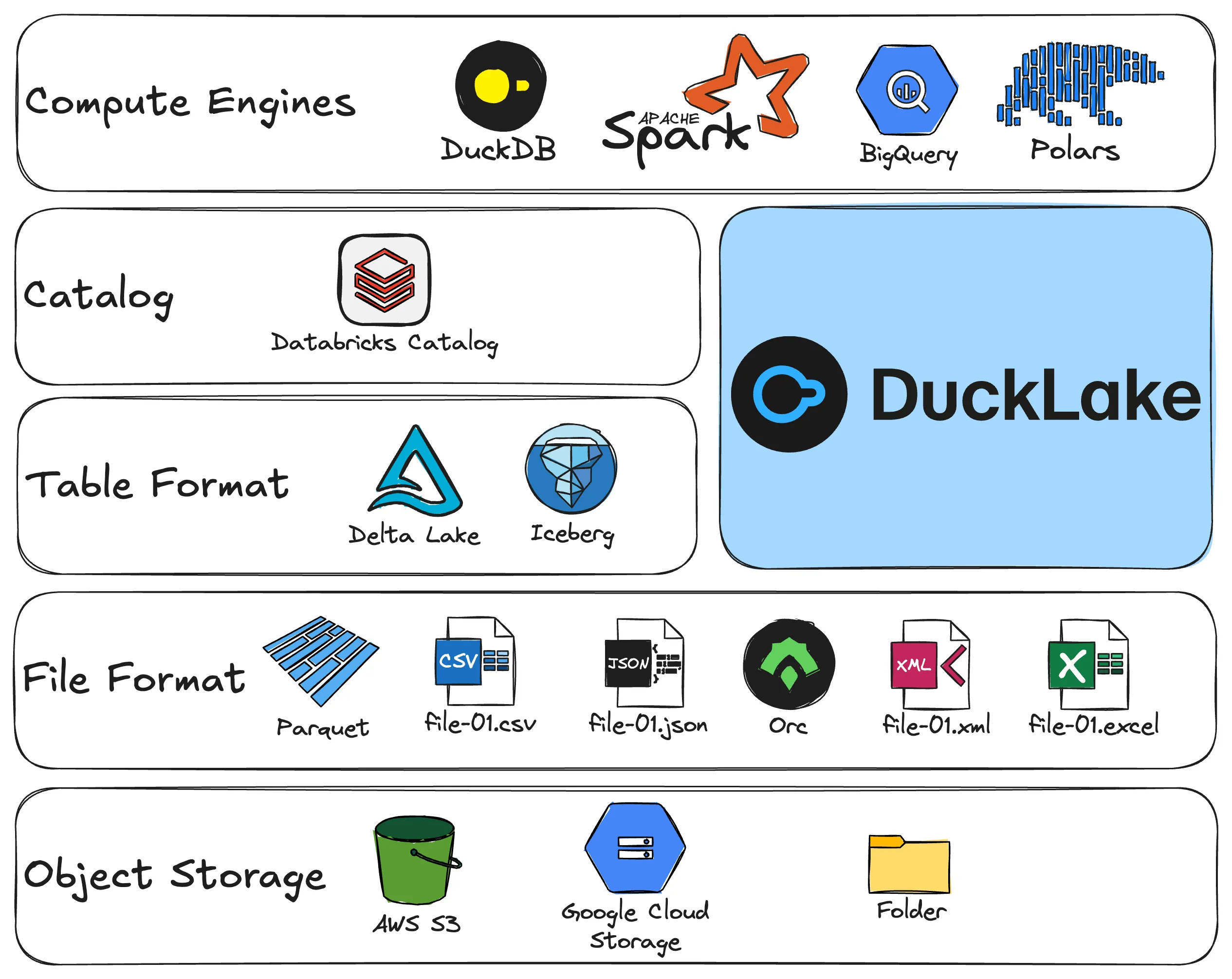

Lakehouse Tech Stack

The Data Lakehouse combines the best of both worlds: the low cost and flexibility of Data Lakes with the transactional integrity and performance of Data Warehouses. By adding this metadata layer, the Lakehouse achieves:

- ACID Transactions: Ensuring safe concurrent reads and writes on object storage.

- Separation of Storage & Compute: Data persists in cheap object storage, while efficiently scalable engines handle the compute.

- High Performance: Using metadata to drive indexing, caching, and file skipping to approach Warehouse-level speeds.

| Data Warehouse | Data Lake | Lakehouse | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Format | Structured Only | All Formats (Raw) | All Formats |

| Cost | High | Very Low | Low (Similar to Data Lake) |

| Transaction Support | Strong (ACID) | None / Very Weak | Strong (ACID) |

| Schema Definition | Schema-on-Write (Strict) | Schema-on-Read | Both Supported |

| Typical Examples | Snowflake, Teradata | HDFS, AWS S3 | Iceberg, Delta, DuckLake |

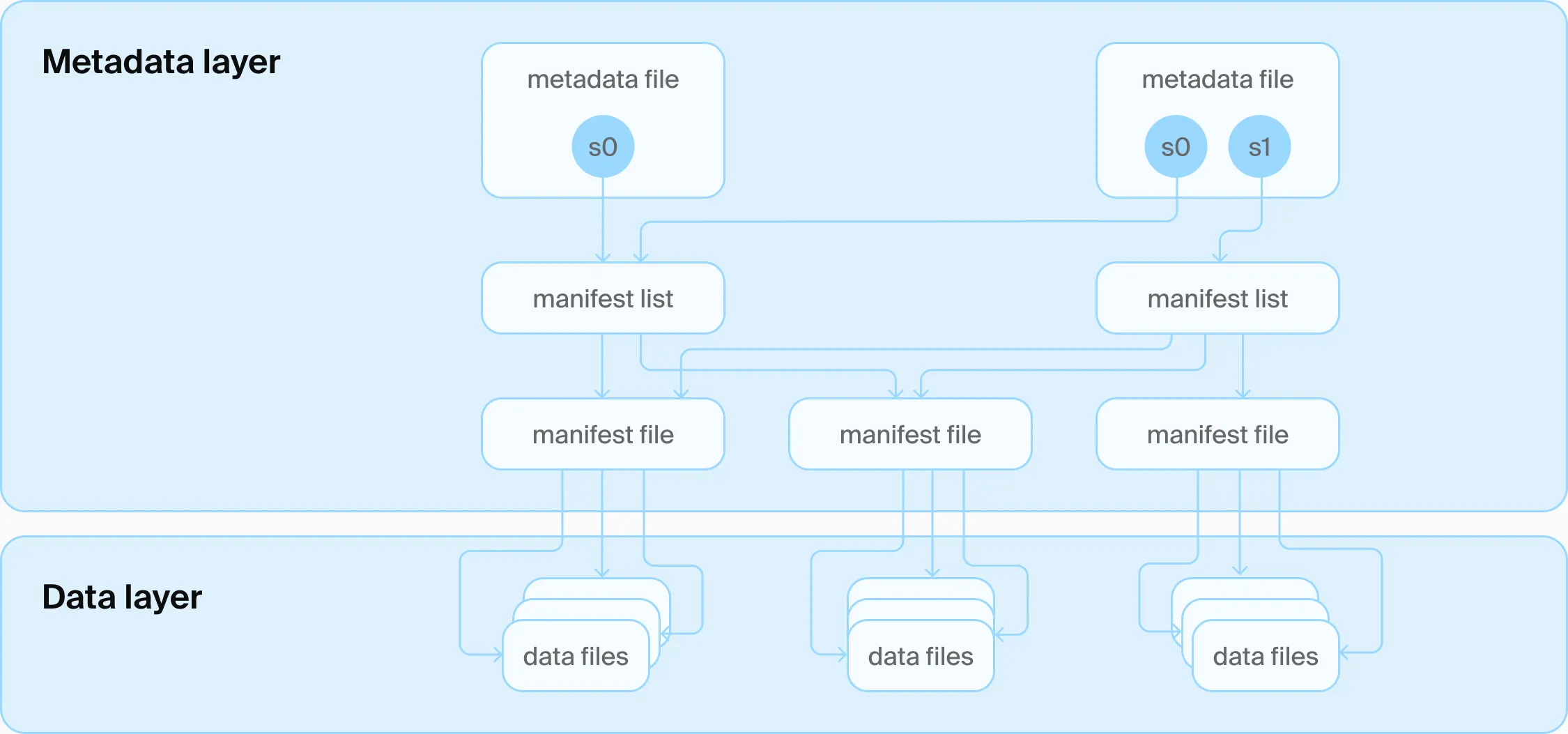

File-Based Metadata

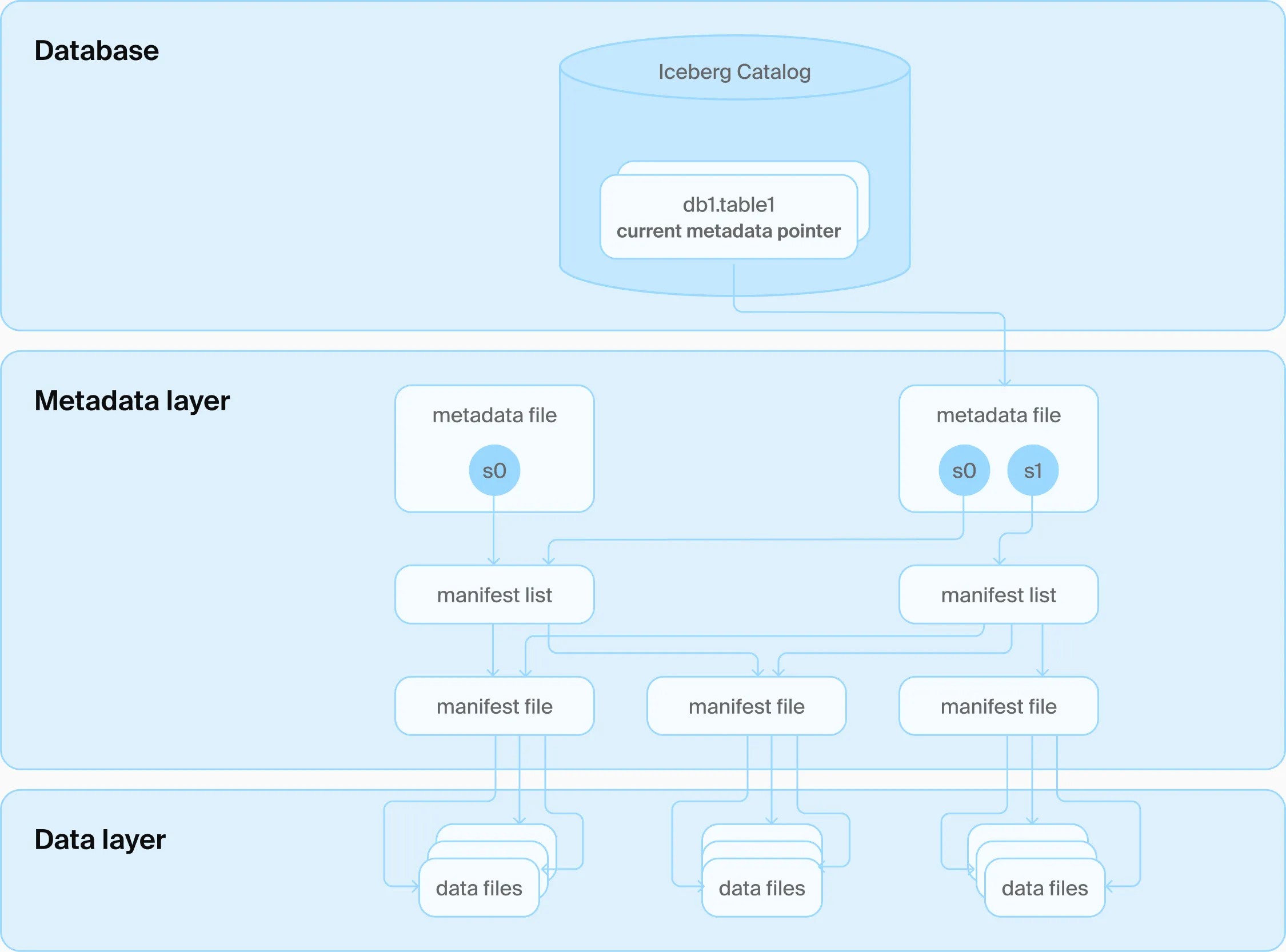

To understand why DuckLake takes a different approach, we must first look at how current leaders like Delta Lake or Apache Iceberg handle metadata. These formats rely on a hierarchy of files stored alongside the data.

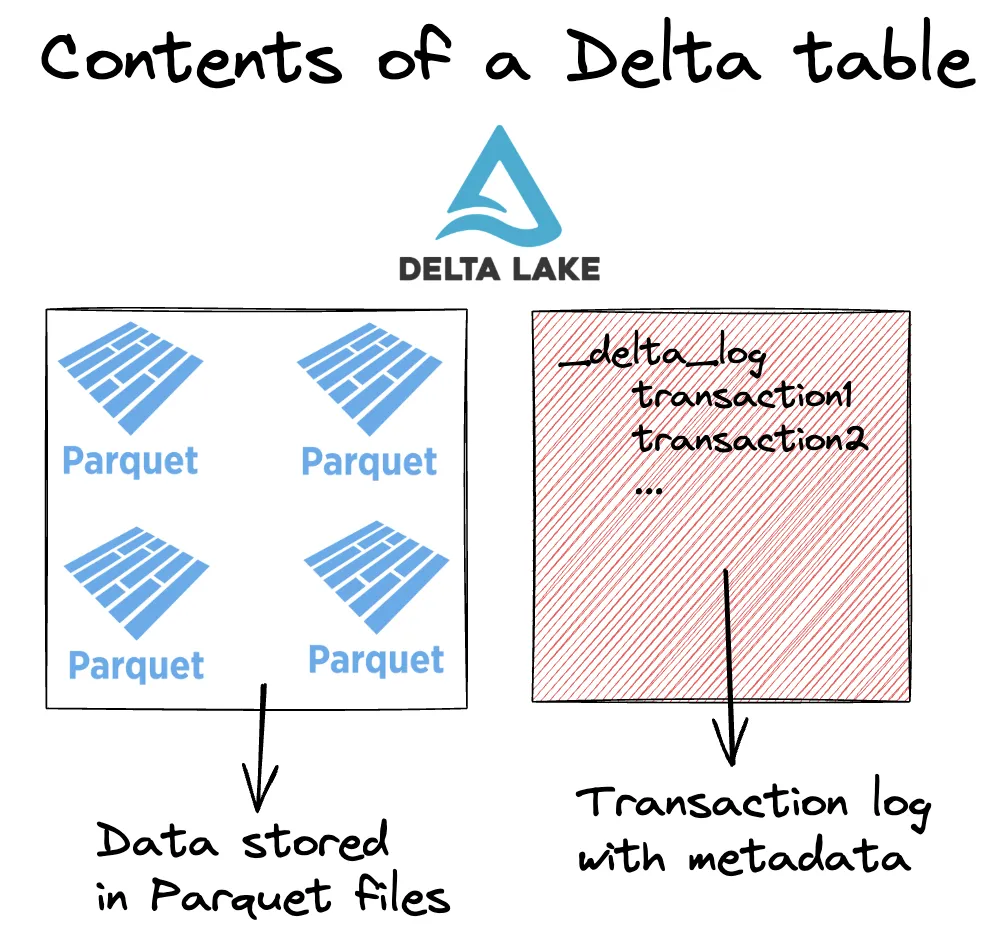

Example: Delta Lake

In Delta Lake, a table consists of Parquet data files and a _delta_log directory containing JSON metadata.

Delta Lake Structure (Source: Delta Lake)

1. Creating a Table

When you write data, a log file is generated.

import pandas as pd

from deltalake import write_deltalake

df = pd.DataFrame({"num": [1, 2, 3], "letter": ["a", "b", "c"]})

write_deltalake("tmp/some-table", df)Directory Structure:

tmp/some-table

├── 0-62dffa23-bbe1-4496-8fb5-bff6724dc677-0.parquet

└── _delta_log

└── 00000000000000000000.json <-- The Metadata2. Appending and Overwriting

Every operation (Append, Overwrite) generates new Parquet files and new JSON log files.

- Write/Append: New JSON entry describes added files.

- Delete/Overwrite: New JSON entry marks old files as

removeand new files asadd.

File-based Metadata Layer (Source: DuckLake)

Generally, for metadata layers:

- Reading data is about finding the corresponding data files and (optionally) pruning files by pushed-down filters.

- Writing data is about generating new data files and updating the metadata accordingly, with ACID guarantees.

The Underside of the Iceberg

Although these table formats look perfect on paper, there is a giant part underneath the iceberg.

Both Apache Iceberg and Delta Lake are just table format. To implement transaction involving multiple tables, they still need an extra catalog layer. These extra stateful catalog services, say Unity Catalog, need extra infrastructure to ensure its availability, scalability, and reliability.

File-based Catalog Layer (Source: DuckLake)

In a Shared-Data architecture, compute nodes are stateless, relying on object storage (S3) to persist state. Since object storage lacks cross-object transactions and objects are immutable, these formats encounter specific issues:

- Network Overhead: Metadata files are of small size and huge amount, which is anti-pattern for object storage. Metadata operations thus lead to high network overhead, and can become a bottleneck.

- Trade-off between Small Write Latency and Visibility: Upon a small batch of writes, direct writes create small-file explosions (amplification); buffered writes cause data latency. High-performance systems must downscale real-time visibility to near-real-time for small write latency.

- Concurrency Conflict: Multiple writers require complex optimistic locking protocols or retries. Most implementations assume a single writer.

- Compaction: The timely merging of metadata files is critical to read performance, while these compactions could cause extra writes to metadata.

Besides, there are functionality that are not specific in the format, but most writers (must) implement them:

- Metadata cache layer

- Multiple writers conflict resolution

- Compaction and vacuum strategy

- …

State is not disappear, it is hidden. This leads us to a core question:

Do we REALLY need the metadata layer to be completely stateless and immutable?

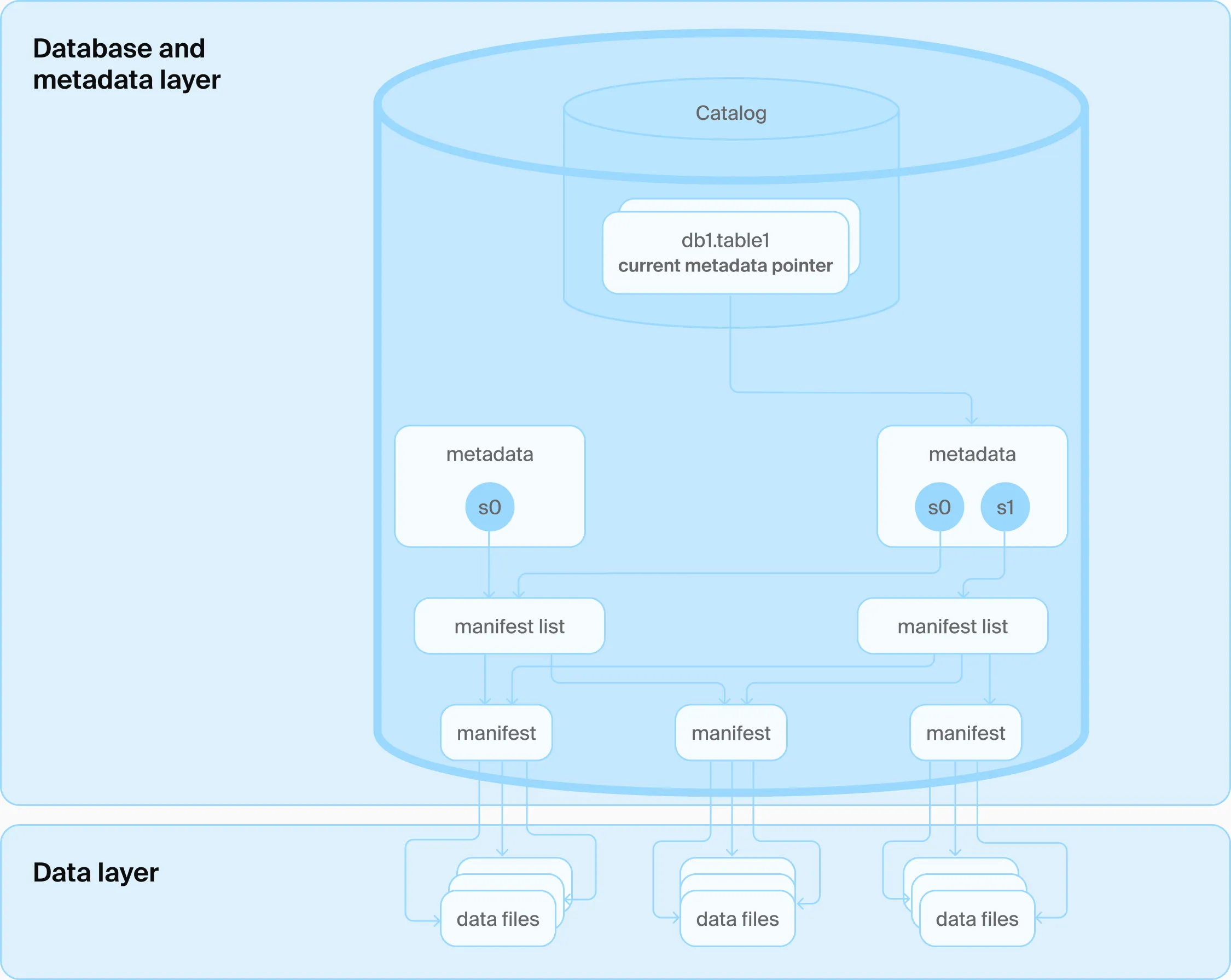

DuckLake: SQL-Based Metadata

DuckLake fundamentally shifts the architecture by using a Relational Database to manage all metadata.

Database-based Metadata Layer (Source: DuckLake)

The idea comes from these discoveries:

- Metadata itself is structured data, and rarely changes schema;

- Metadata is tiny: for 100TB of data, you might only have ~1GB of metadata. This scale is easily handled by a single-node database instance (PostgreSQL, SQLite, or DuckDB itself);

- Even if you need scaling-out, read replica, high availability, you name it, Database people handle it way better!

The Architecture

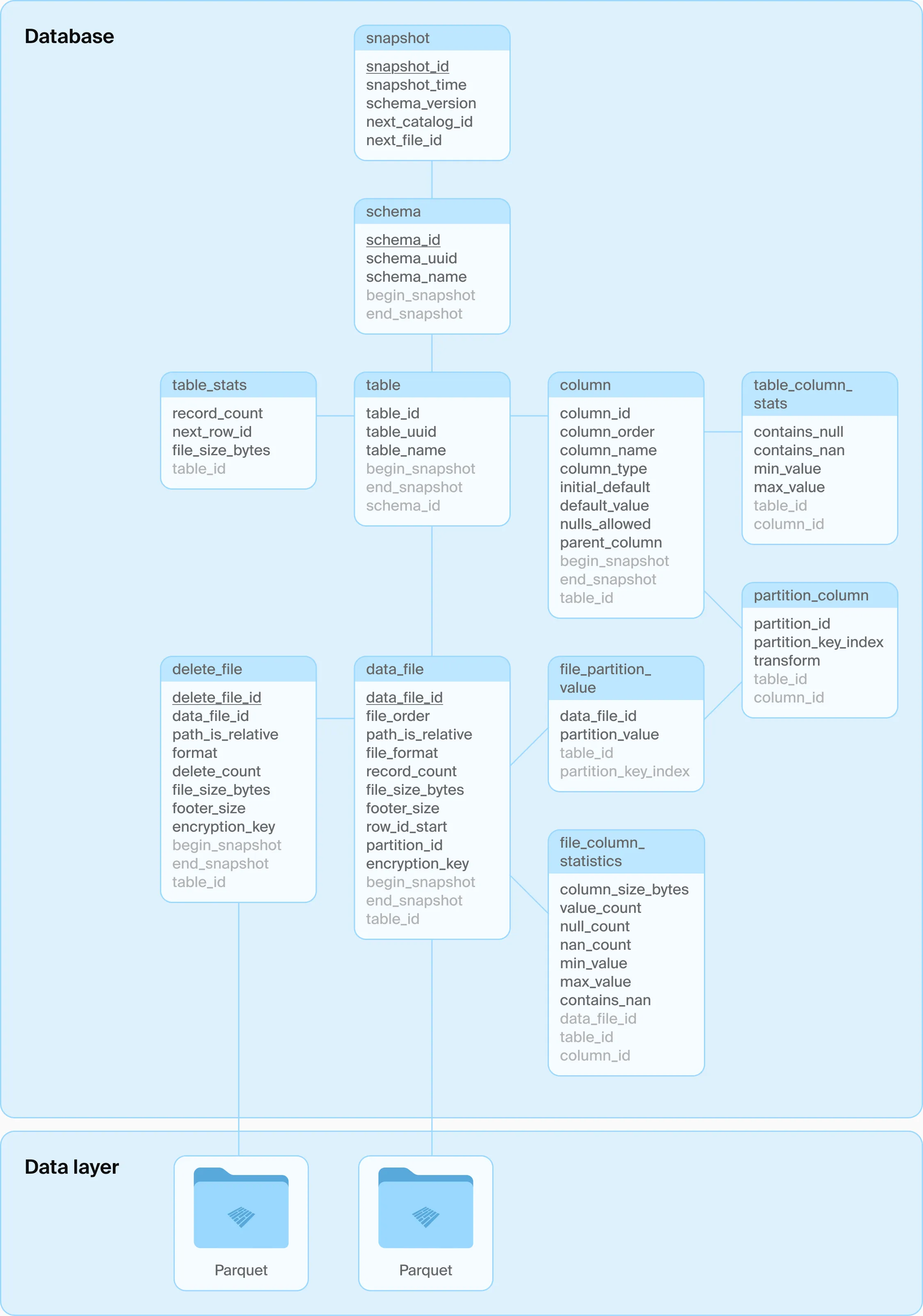

Instead of parsing thousands of JSON/Avro files, DuckLake operations become standard SQL queries.

Ducklake Metadata Schema (Source: DuckLake)

Reading Data, or locating the correct files for a snapshot, happens in a single SQL query:

-- 1. Find the latest snapshot

SELECT snapshot_id

FROM ducklake_snapshot

WHERE snapshot_id = (SELECT max(snapshot_id) FROM ducklake_snapshot);

-- 2. Find files associated with that snapshot

SELECT table_id, table_name

FROM ducklake_table

WHERE

schema_id = SCHEMA_ID AND

SNAPSHOT_ID >= begin_snapshot AND

(SNAPSHOT_ID < end_snapshot OR end_snapshot IS NULL);Writing Data first store the raw Parquet file to storage (S3/Local), and then update the metadata tables in the database via, again, a standard SQL Transaction.

Concurrency and Transactions

Concurrency is offloaded to the database engine.

- Conflict Detection: Every write increments the

snapshot_id. If two transactions attempt to commit, the database’s primary key constraint onsnapshot_iddetects the conflict. - Resolution: DuckLake records changes in a

ducklake_snapshot_changestable. If a conflict occurs (e.g., dual inserts), the logic can check if the changes overlap. If they don’t, the transaction can simply retry the metadata commit without rewriting the heavy Parquet data.

Note: As of this writing, high concurrency on the snapshot_id can be a bottleneck in DuckDB extension implementation. In pg_ducklake we have planned future optimizations about utilizing PostgreSQL’s conflict resolution.

Compaction/Vacuum

Currently, DuckLake extension supports two types of compaction:

ducklake_merge_adjacent_files: Merging small files.ducklake_rewrite_data_files: Merging data files with delete files.

A compaction strategy is about choosing files to compact and modifying the metadata. Because metadata is SQL in DuckLake, extending or customizing compaction strategies mostly involves changes in metadata queries, which is significantly easier than with file-based formats.

Data Inlining

A unique feature of DuckLake is handling “Small Writes” via Data Inlining.

Instead of writing a tiny Parquet file to S3 for a single row insert, DuckLake caches this data directly in the metadata database as part of the format specification. The inlined data will be stored in a table of metadata database, with a name ducklake_inlined_data_{table_id}_{version}.

This data is immediately visible to readers. When the buffer grows large enough, a background process flushes it to a Parquet file. Once again, the flush threshold and duration are easily configurable through simple SQL changes.

Closing Thoughts

DuckLake represents a return to simplicity. By leveraging the decades of maturity in SQL databases for metadata management, we solve many of the consistency and latency headaches associated with file-based Lakehouse formats.

Why DuckDB?

“Wait, this idea sounds so straightforward, doesn’t anyone think about it?”

Yes, most, if not all, catalog services are based on database actually (say Unity Catalog). But they exports a RESTful interface (Iceberg REST catalog API, etc.) to compute engines, instead of SQL interface.

DuckDB is distinct in its ability to run anywhere. Whether a CLI or Python library from a laptop, or embedded in other databases. It can operate as a stateless engine over S3, or effectively act as the catalog database itself. The ducklake extension provides a standard reference implementation that is easy to integrate.

Why pg_ducklake?

In pg_ducklake, we are working on a tighter integration between the metadata layer and the PostgreSQL database. We find that DuckDB and PostgreSQL can work well with each other.

With embedded DuckDB, PostgreSQL now provides:

- Analytical engine.

- Native columar storage and lakehouse.

Embedding inside PostgreSQL, DuckDB with Ducklake extension can:

- Bypass remote connections, metadata optimization becomes native to PG;

- Single-concurrency small writes can go directly to the “Inline” tables in PG (faster than remote DuckLake).

- High-concurrency conflict detection utilizes PG’s internal locks, significantly boosting QPS.

pg_ducklake is under active development, and we’re eager to hear from the community.